Just a video game?

One legitimate question about professional driving simulators is how they differ from racing/driving video games. One of the most successful video game of the past decade is Grand Theft Auto 5, which features realistic environments, multiple vehicle types, pedestrians, realistic enough physics, etc. It has notoriously been used in multiple AI training projects (see Grand Theft Auto V: The Rise And Fall Of The DIY Self-Driving Car Lab).

Everything we want in a driving simulator, right?

Well, yes and no.

The first thing is that in a similar way that a game is a product in itself, so is an experiment. We need a way to develop that product. Which means that what really interest us are the tools and the assets used to make that game. Tools and assets that we could reuse to make our game, our experiment.

Game Engines

That’s where game engines appear. Those are the tools made to create any modern game. Grand Theft Auto 5 was made with a proprietary game engine, and we obviously can’t simply get our hands on it and create our own city and our own scenarios.

There currently are two major game engines available for anyone: Unity and Unreal Engine. Any of those two is a great starting point to making your very own driving simulator.

What they do

Out of the box, game engines offer a wide variety of features that we need for our driving simulator, and for our experiments.

The most obvious one is an editor to create virtual world. Creating a scene, adding trees, buildings, etc. It’s simple and thoroughly documented. Researchers may not necessarily be skilled in programming, but worry not! Those tools are also made for “level designers”, that for the most part don’t write code. So there is a good overlap of the target audience.

But it’s not just that, game engines offer vehicle dynamics, controller mappings, sound spatialization, basic AI, characters, and most importantly: the ability to add and modify anything you want, either by creating it yourself, or by purchasing someone else’s work on their store, which features thousands of assets and plugins that will save you a lot of time for not that much money.

What they don’t (necessarily) do

Game engines might get you pretty far by themselves, but they won’t cover everything you need. When using driving simulators in a research context, there still are some requirements that are too domain-specific to have a ready-to-use solution.

Data recording

The main reason why we run experiments is to study people’s behaviour. And to do that, we need to record data. Part of that data will be external to the simulator (e.g. physiological, video), but part of it comes from within the simulation. There are a lot of driving-related measurements that we tend to use, such as:

- Speed, acceleration

- Lane border distance

- Headway

Not only do we need that data to be recorded somewhere, but we also need it to be synchronized with all of the other data sources, which depending on your study field might vary.

And for some data, computing it in the first place is quite challenging. Take the “Lane border distance”. In a game engine, the lane border is just another polygon that’s rendered on screen. It has no logical existence. So how do we compute that value?

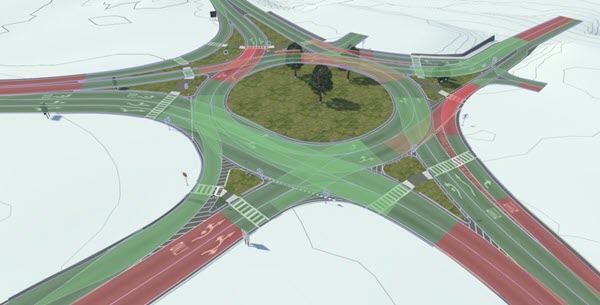

Road network

To answer the question above, and to easily create realistic actors in our scenarios, we need to have a logical description of the road network. We need to know where are the roads, the lanes, the junction, the sidewalks, etc.

Thankfully, standards already exist to describe such data. The predominant one is OpenDRIVE, and is commonly used as “HD Maps” for CAV.

With such network descriptions, it becomes easier to compute most of the driving-related data needed for our studies. And it also becomes easier to populate the scene: if you know where the roads are, you probably can somehow tell a car to “stay on its lane”. However, to get that data into the engine, you’ll have to do it yourself!

CAVE rendering

Even with the rise of consumer-grade VR headsets, CAVEs are commonly used for high-end driving simulators. They come in various shapes and sizes, but the idea is the same: cover the widest field of view to fully immerse the participant.

CAVEs come with a great challenge: how do you render on all the screens? Whereas a video game might run on a wide-screen, here we’re talking 360° of field of view, with multiple 4K screens. A single computer won’t be powerful enough to render on all screens. So you’re going to have to somehow distribute the rendering across a cluster, and synchronize it so that all screens display the same scene state at the exact same time. Not a small feat to accomplish.

What we’ll talk about next

In the coming posts, we talk deeper about the choices we’ve made for our driving simulator, the good and the bad of game engines, and how we’ve managed to work around their shortcomings. All that when being a team of mostly one person, for which making a driving simulator isn’t really in their job description.