VR Headsets

For the past ten years, the world of Virtual Reality headsets has been redefined, lead by Facebook’s Oculus and HTC’s Vive. Those relatively cheap devices allow for better immersion in various types of environments, and are now being used in a wide range of both industry and research entities. But, even though we’ve previously mentioned use of CAVE simulators, we never talked about VR headsets. Why is that?

Why we don’t use them

The title is voluntarily misleading, as we own and use multiple VR headsets, but not for driving simulation just yet. The technology has been and is still improving a lot, and we’ve been playing with 3 generations of headsets for over 5 years now; using them for demos, pedestrian simulation or just internal testing. But we haven’t used VR headsets for any driving simulation experiment, nor do we have any planned in the short term. And there are multiple reasons behind that.

Low resolution

HTC recently announced its Vive Pro 2 with a single eye resolution of 2448×2448, compared to the original Vive’s 1080x1200. So there’s a lot of progress on the resolution front, but is that enough for driving simulation? I’m still not sure.

On a driving simulator, you need to be able to see a lot of things, far and accurately. When driving at 90km/h, you perceive objects that can be well over 100m and cover only a very small fraction of your field of view. If drivers can’t make up what it is they see in the distance because there’s not enough pixels, that’s a big issue. As a consequences, drivers might alter their driving behaviour for simulation reasons, which is something we try to avoid as much as we can (even though we obviously can’t totally get rid of).

You also want to see your dashboard with as much accuracy as possible. Nowadays, needle displays tend to disappear for more digital interfaces, but there’s still a lot of information on the dashboard (or infotainment system), which is often hard to read on VR headsets.

Head data

At LESCOT, we study driver’s behavior, and in order to do that, we use multiple data sources related to the head of the participant, which can be incompatible (to some degree) with VR headsets.

Historically, we’ve been using video recordings of driver’s face to gauge their reaction, expressions, or more recently emotions. With a headset covering half their faces, this becomes pretty much impossible.

Both EEG and fNIRS require sensors over most parts of the head, which is usually not compatible with headset straps. Those measurement devices are commonly used in our experiments, so it’s easier to have them in our existing monitor-based simulators.

We also make heavy use of eye tracking, though on that front, more and more VR headsets started integrating such features (e.g. Vive Pro Eye), mainly driven by the prospect of foveated rendering.

Car interaction

In a driving simulation, your hands are mostly on the steering wheel. But by default, you don’t see your hands in VR! So right off the bat, we’re faced with quite an immersion breaker: your hands will hold a steering wheel in the real world, while in the virtual world, you would just see a steering wheel, but no hands.

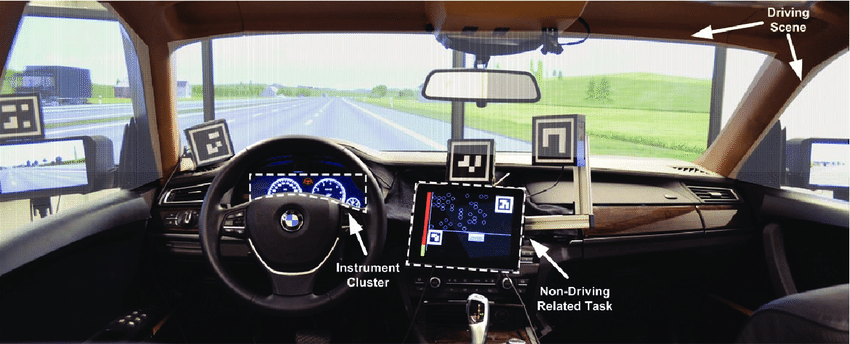

And that’s the tip of the iceberg. We often use what we call “non-driving related tasks” (NDRT), which most of the time is a side screen which the driver has to interact with, most of the time to play a small game.

All that in a VR headset would be challenging to say the least. You could probably design a new NDRT that don’t require physical interaction (i.e. no touchscreen), but that would obviously be very difficult. Integrating a side display into the virtual car is also a challenge on its own, as you’ll once again face the resolution issues mentioned previously.

Overall, during the experiment, the driver might have to interact with a lot of things in the real car. Being immersed in a virtual car, without visible hands, is too much of a hassle in most cases.

Mirrors

I’ve already talked about the challenges of mirrors on CAVE simulators, but it’s not a walk in the park in VR either.

First, we obviously still have the same resolution issue as mentioned above: the mirror covers a small fractions of the headset field of view, therefore only few pixels are available to render it. But that small space contains a lot of information, and you need to be able to see it as clearly as possible. In our CAVE-like simulator, we use 1920x1080 displays for mirrors, but even with a Vive Pro 2, I doubt that you can get even 10% of that resolution for mirrors.

Mirrors are also very costly, in terms of computing power, to render. Each mirror is basically equivalent to rendering the scene once more. And we have 3 mirrors. Once again, on our clusters, we have dedicated computer for each mirror, as each one is a monitor. That’s not possible with VR, as only one computer can render the whole scene. By the way, with a Vive Pro 2, to render a scene properly, you have to generate two (one for each eye) 6MP (2448x2448) image in 8.3ms (120Hz). That’s a throughput of 1.43Gbps, compared to 124Mbps for “classic” display (1080p60Hz). If you want to render mirrors on top of that, you’ll have to turn the visual quality of your simulation way down.

Why we will

Even with all those issues, I still think we’ll use VR headsets for driving simulation in the near future. Probably not for all experiments, as some problems just don’t have easy solutions. But VR headsets also have a lot of benefits, and new products are tackling some of the shortcomings discussed in the previous section.

New tech

We don’t currently own a Varjo XR-3, but I hope we will soon, because this headset seems to solve multiple of our problems at once.

First, they have a very smart feature, which is similar to foveated rendering, except it’s hardware: they have a 4MP display dedicated to the focus area (27°x27°), which follows your gaze thanks to eye tracking. So that should solve both the resolution and eye-tracking at once, right?

Not only that, it has mixed reality! Thanks to their high resolution and cameras, the headset is able to create impressive augmented reality. This demo showing helicopter simulation with a real-world dashboard is pretty close to the perfect solution for our interaction and hands issue.

On another front, Manus has motion tracking gloves, which makes it possible (and easy) to see your hands in VR, and opens the door to more cockpit interactions.

No more CAVE!

Running an experiment on a CAVE-like setup like ours is costly, both in time and money. Our most advanced simulator runs on 13 displays, powered by 9 computers. That’s not cheap to install, and not cheap to maintain. You have to handle networking, synchronization, cables, sessions, etc. Just powering the thing on is its own little adventure. When building an experiment, there’s always a pretty big gap between getting the scenario running on your desktop and getting it to run on the simulator cluster. And a major part of my job is solving issues related to the latter.

So a VR headset would make everything easier, cheaper and faster. And by a wide margin. So at some point, those benefits will outweigh all the issues identified earlier.

For now, we use lightweight headsets (e.g. Vive Cosmos) during experiment development, so that researchers and developers can test their scenarios from their desktop (or their home office!) with high immersion, therefore making test runs on CAVE simulator less frequent.

So even if the VR “revolution” hasn’t reached driving simulation yet, it doesn’t mean it won’t. And I sure hope it will.