Angular size of partially occluded actors

A researcher colleague recently asked me: “Could we get the angular size of an actor in realtime, even if they’re partially occluded?”. As with many things in Unreal Engine, the answer is “yes we can!”, so here’s a breakdown of our answer to this question.

The problem

Angular size…

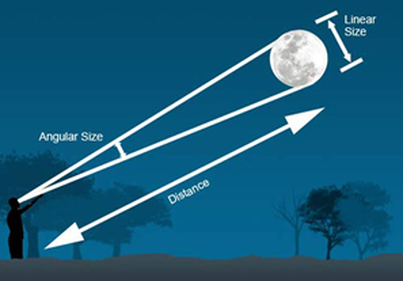

Angular size, visual angle, angular aperture, etc. are, in our case, all synonyms of what we want to measure. To quote from Wikipedia:

The angular diameter […] is an angular distance describing how large a sphere or circle appears from a given point of view

In our field of study, it can be a useful indicator of the visibility of actors in the scene from the driver’s point of view. I won’t go too deep in the actual scientific use of this measure, as this blog discusses more the how and not the why (researchers cover that part in their publications).

… of actors…

As the definition above points out, angular size works if the target is a sphere (or projects as circle). But in our case, we’re not really interested in the angular size of a distant planet, but actually of scene objets.

And those can be of any shape: pedestrians, street signs, roadside props, bikes, and so on. So how does the definition of angular size apply to a not-so-spherical pedestrian? Should we take the height? The width? The average? And pedestrians can move their arms or legs, carry objects, which can all impact the angular size.

… partially occluded

Not only do actors have widely varying shapes, but they can quite often be partially occluded! A pedestrian can be partly behind a trash can, or a street sign can be somewhat masked by a tree.

This “occluded” requirement actually makes any solution much more complex to design: the size of an actor could be approximated statically, but the occlusion is inherently dynamic, and therefore needs to be solved at runtime.

Our solution

When I sat down to design a solution, two different approaches came to mind. I’ll go over the one we actually implemented, which is CPU-driven. And I’ll mention at the end the one we didn’t, which is GPU-driven.

The overall idea is to first, figure out what parts of the actor are currently visible. Then, we need to approximate those parts as a shape on which we can compute an angular size.

Visibility check

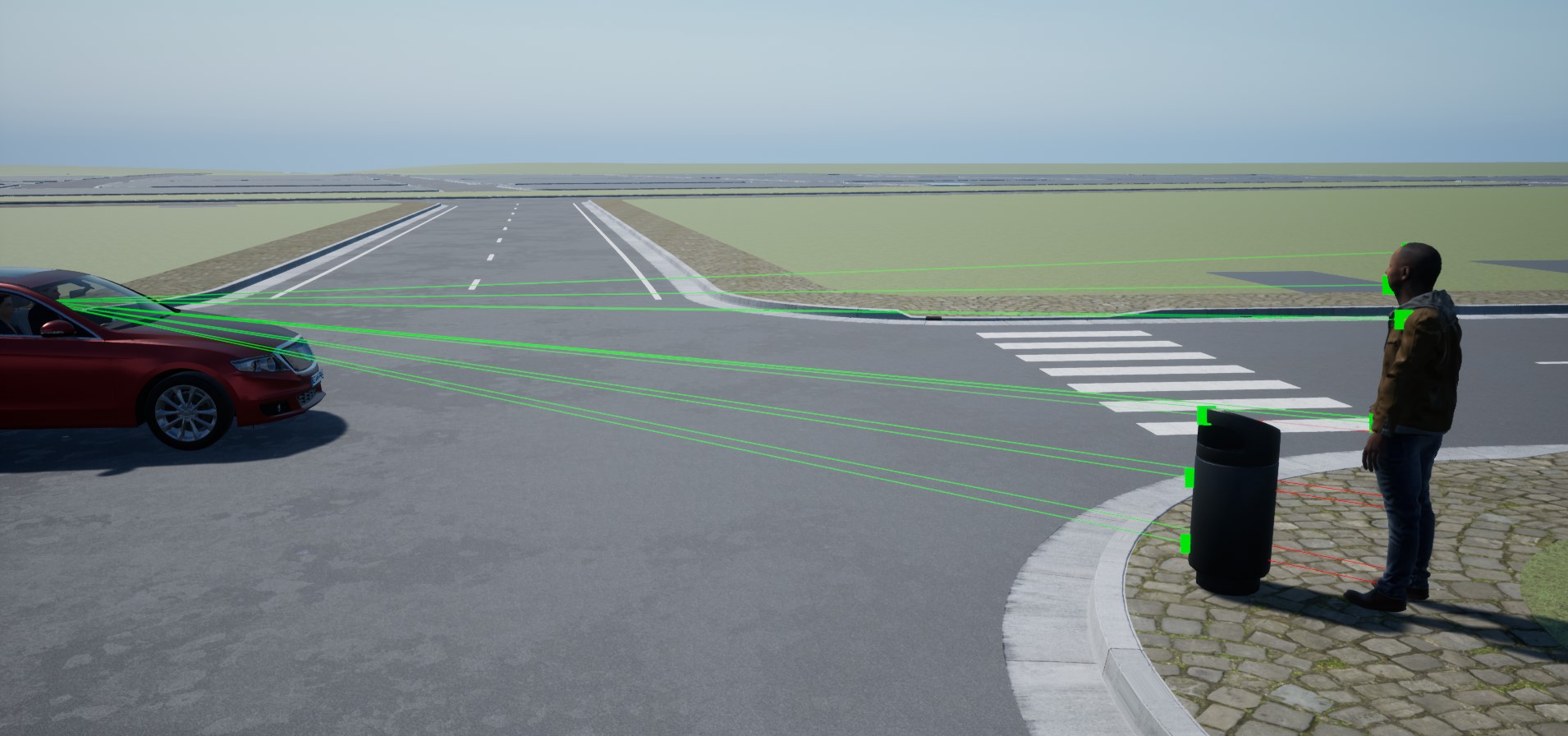

In game engines, if you want to check if something is visible, you “trace” it. However, traces work as a single line, or as a fixed-size shape. So if we were to trace a pedestrian, it would only check its root position and returns whether that was visible or not.

However, most pedestrians have a skeleton, which is used to animate them. And as with real-life skeletons, virtual skeletons also have bones. What if we traced bones?

That’s the solution we chose: for each type of actor we wish to get data from, we define the set of bones (or sockets) that we’ll trace.

This has a lot of benefits

- Bones carry semantic information (e.g. head, foot), so we know which parts were and weren’t visible.

- For each trace, we can know the occluder if it didn’t hit its target

- For a single actor, we can trace multiple meshes. For instance, for a biker, we can trace the bike and biker bones.

- We can select the level of accuracy we want by selecting or excluding bones from the traces. For example, for most pedestrians we don’t really care about each finger visibility. But in some specific use cases, we could…

The one major downside, however, is performance cost. Even though tracing is highly optimized in Unreal Engine, we can’t just trace 20 bones on 40 actors at each frame. Our main solution for that is to only trigger this process when we need it: from our scenario, we roughly know when an actor will be relevant to ego. Another unexplored solution could be to distribute computation over our nDisplay cluster. Instead of having a single computer tracing 5 actors, why not have each computer of the cluster trace one? We’re far from being CPU-bound on our cluster, so that actually could work.

Another downside is inaccuracy: traces use the “physics” version of the world, which can differ from the “visible” version. Collisions (which traces are a part of) use a simpler world, with geometry that’s much more efficient to work with than rendered objects. On top of that, collision geometry is unaware of rendering tricks that can alter the object shape, such as World Position Offset (WPO). Those tricks are commonly used for moving foliage (e.g. simulating wind on tree branches), so we have to be very aware of this limitation.

From bones… to angular size?

Ok, so line traces can tell us which bones are and aren’t visible. But how do we get an angular size from that information?

To answer that, we first have to go back to a question mentioned above: what’s the angular size of a non-spherical object? Well, I was rather lazy on that one, and I decided: why not make everything a sphere? Game engines use a lot of bounding volumes (e.g. bounding box), and it’s not uncommon to approximate actors as their bounding sphere for some rough estimations (because spheres are really easy to work with in 3D). In our case, it’s a good enough estimate, as the bounding sphere’s diameter is equal to the largest visible size of the actor in the eye frame. To explain that better: for a 1.7m standing human, the bounding sphere will be 1.7m (unless they span their arms wide), which in terms is kind of ok for our angular size computation.

Now that we decided that everything would be approximated as a sphere, how do we turn our list of visible bones into a sphere? Well, Wikipedia to the rescue! It turns out that smart people out there figured out a way to compute the minimal bounding sphere for a series of points. So we implemented Ritter’s bounding algorithm, which though slightly inaccurate, is more than enough for us (and trivial to implement). The code is available on Epic’s Developer Community.

And after that, it’s basically over! Once we have the bounding sphere, it’s just a matter of arctan to get the angular size, and solve the issue that we were dealt with.

There are still some weird cases that are hard to figure out. For example, if a pedestrian has its chest occluded (e.g., by a sign), but head, legs and arms visible: what’s the angular size then? Currently, our implementation returns the bounding sphere for all the visible bones, which actually encompass the whole body, including the occluded chest. Is it valid? Probably not. Should we instead take the largest subset of continuous body parts? Maybe. Or maybe the answer is that the angular size simply doesn’t really exist in such cases.

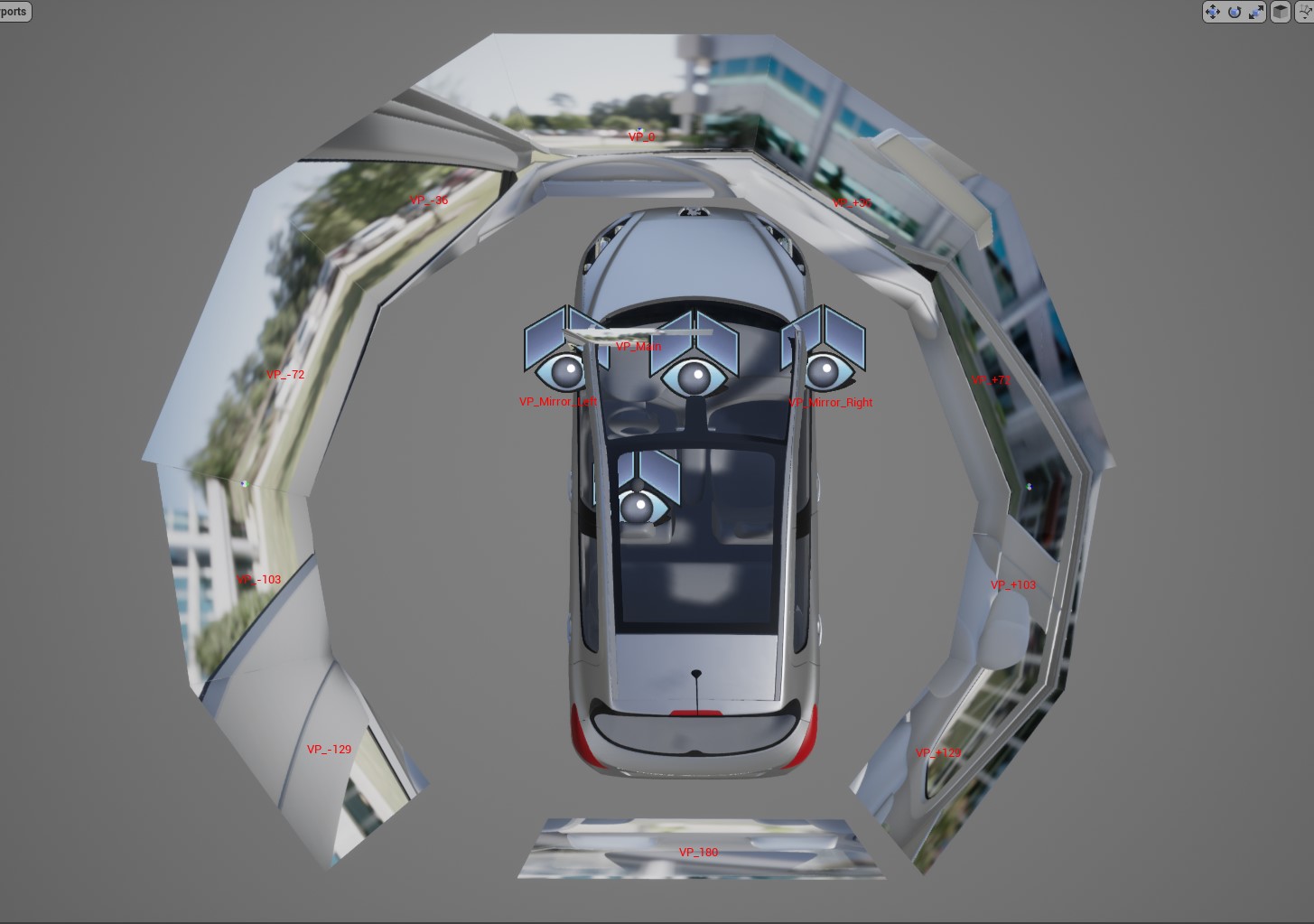

Mirrors

Car mirrors have saved countless amount of lives around the world, but as a driving simulation developer, I really hate them. They’re the reason why we can’t have nice things: they’re tricky to implement in nDisplay, they destroy framerate in VR headsets, they’re hard to configure properly in 3D engines (aspherical mirror), and they require additional work to include monitors (with weird aspect ratios) on any real-scale driving simulator hardware.

So once again, mirrors are here to ruin my life. Because of course, computing angular size from the driver’s point of view is nice, but what about mirrors? Actors can also be visible through them… Well, my life wasn’t actually ruined, because we can access the nDisplay configuration at runtime (using the nDisplay Root Actor), get a hold of the mirror’s camera location, and do all traces from there also. This obviously has a performance impact, but we added an option to select which sources will be used for any traced actor, as once again, we know from which viewpoint actors will be visible based on our scenario design.

Actually, my life was kind of ruined still, because that doesn’t really work. Indeed, traces don’t know about the actual viewport size, so they’ll continue to hit even if the actor isn’t actually visible in the mirror, but is visible from the mirror’s viewpoint. Also, since the ego vehicle is ignored by traces (to not hit the actual mirrors), any actor occlusion by said vehicle is also ignored. Both of these could probably be solved (resp. using multi line trace and a mirror/windows-less chassis), but by now my laziness has taken over.

Another way

The solution outlined above is all done on the CPU; but as I mentioned earlier, there (probably) is a faster, cheaper, more accurate GPU way. I haven’t explored it much, so I’m mostly going to throw random ideas at you. It’s going to get technical, so bear with me.

You can fairly easily write a post-process shader that renders (e.g., to the custom depth buffer) only the visible parts of your target actors, similar to image segmentation. That image would probably be black, with only white pixels where your actor was.

The white pixels are actually just like our traced bones: they don’t tell much by themselves, and we need to cluster them if we want to be able to compute an angular size. This is where is gets trickier, because ideally to do that you’d get OpenCV and be done with it. But our image is on the GPU, and any OpenCV post-processing would require the image to be readable from the CPU. There are ways to bring things from GPU memory to CPU memory, such as screenshot (look at that nice bMaskUsingCustomDepth parameter), or maybe UnrealCV, but I doubt those can be used in realtime.

But, and this is not a rhetorical question: could this post-processing be done in a post-process shader? I honestly don’t know the answer to that, but given the level of shader magic I’ve seen, I wouldn’t be surprised if it could. For example, if you could just count the number of white pixels on the input image, write that number on a pixel of the output image. Then maybe from the CPU you can query that pixel? I truly have no shader skill, so maybe I’m just spewing garbage ideas around.

In any case, working on the output from a render pass would have benefits over our traces implementation:

- Lower performance cost

- Better accuracy, as we’re working with actual rendered data, so no relying on approximate physics bodies, or being tricked by WPO

- Mirrors aren’t really a problem anymore

The only drawback I can see is the loss of semantics that bones provide, i.e., it’d be much harder to know which part were and weren’t visible, or what was the occluder.

Conclusion

Our current traces-based implementation works great for us. We haven’t measured the performance impact just yet, but we’re not too worried about that. For each actor of interest, we actually compute a few other indicators related to visibility that are near-impossible to compute offline. And all that data is then sent via LabStreamingLayer to be recorded and synchronized with other experiment data.

Once again, Unreal Engine really empowers our research. But this time, not by allowing us to create more immersive worlds at lower costs, but by giving us access to measures that will be hugely beneficial to our research, and that were previously completely out of our reach.