Scenario Variants

The basis of a driving simulation experiment is the scenario. But quite often, an experiment requires not one but multiple scenarios. And most often, those multiple scenarios can be described as some kinds of variants from one another. How do we structure our experiment around this variant concept?

What’s a variant?

Before getting into it, I’ll first mention that this subject is closely related to the Design of experiments, including all of its problematics (e.g. learning effect). As this is a tech blog, I won’t cover any of those aspects.

To get better insights into driver’s behavior, one way is to immerse them in not just one situation, but multiple variants of that kind of situation, and study how their behavior varies based on the situation differences.

The most obvious variants are the ones directly related to the study itself. I’ll take as example a hypothetical study, in which we want to study driver’s acceptance of various AEB behaviors. Those different behaviors are our most obvious variants. And we could stop at that, having the exact same scenario and situation played for each AEB behavior and call it a day.

But for various experimental design reasons, we might want to add other varying parameters. For example, we might want to test AEBs in different situations, such as the type of pedestrian (e.g. adult, child) running across the road and triggering the AEB. We might also want the situation to not always occur at the same place in the scene, and at varying length of times after the beginning of the scenario.

The more you add varying parameters, the more complex your experiment gets. Let’s say you have 5 AEB behaviors and 3 pedestrians types, that’s already 15 variants. Some people would actually create 15 scenarios, involving a lot of copy/pasting and therefore being very error-prone in the long run (e.g. if you then want to slightly change one AEB behavior, you need to do it in all scenarios involving that AEB).

Implementing Variants

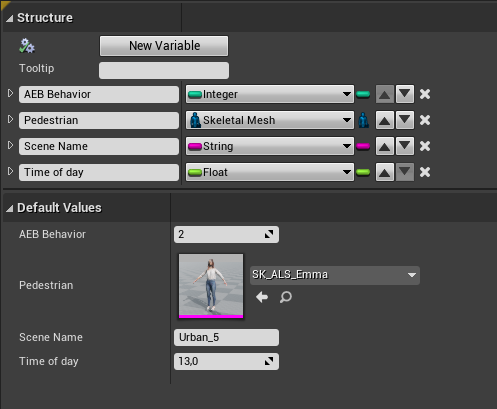

So, how do we tackle that problem? The first step is to define what our variants will be. In Unreal Engine, this can be done in a few clicks with Structures.

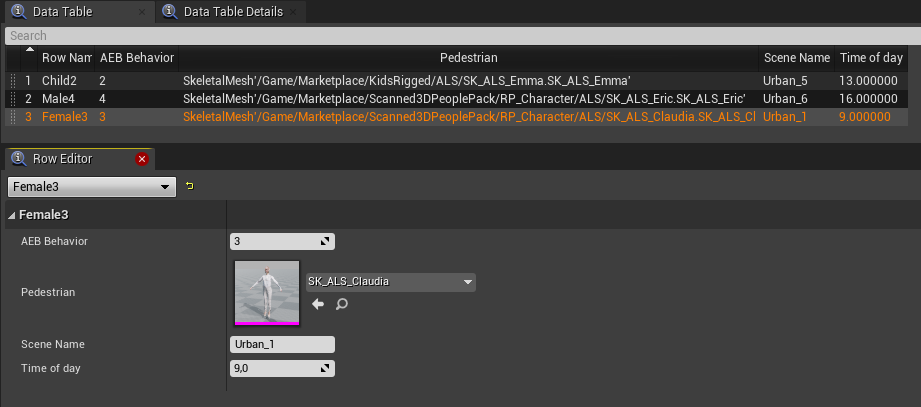

Now that we have defined what “a variant” will be, we need to define the actual list of all the variants that we’ll want to have. To do this, we use Data Tables, which are pretty much simple spreadsheets, with columns matching a… structure! So if we simply give the Data Table our newly created Structure, we can then fill it with our variants.

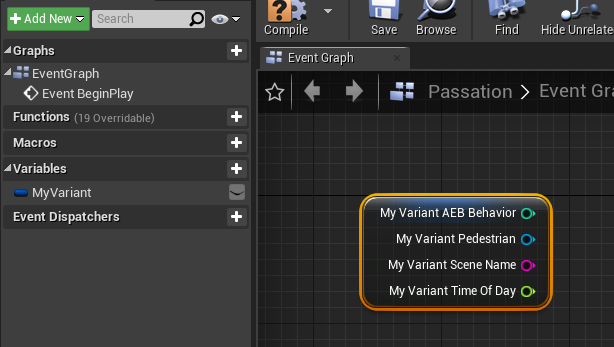

And with all that, it’s time to actually build the scenario as you would usually do, except you can load variants from the Data Table into your Level Blueprint, and then use all the values as parameters into your scenario. I won’t get into the details of how to load each variant, and then how to properly sequence them (in various orders) as it’s a whole other subject. Feel free to get in touch if you want to discuss it further.

This system is very flexible, as you can change a variant without ever touching the scenario. This proves useful if the researcher, who specifies and tunes variants, isn’t actually implementing the scenario. Using our variant system, the researcher can simply edit the variants from the data table and immediately test the scenario to have feedback and adjust accordingly.

And if during your initial tests, you realize that you need another varying parameter (e.g. weather condition), you just add an attribute to your Structure, update the new Data Table column with the values you want for this attribute, and update the scenario to now use and apply this variable.

Am I re-inventing the wheel?

The Variant Manager is a specialized UI panel in the Unreal Editor that you can use to set up multiple different configurations of the Actors in your Level. Each of these configurations is referred to as a Variant.

At some point, I have to mention Unreal Engine’s own Variant Manager, as it seems quite similar to what we’re doing.

While it is indeed pretty similar in the idea, I find the implementation lacking in several factors, which lead me to our custom Variants implementation.

First, the Variant Manager uses unstructured variants, i.e. there’s no Structure defining what a variant must be. This means that for each variant, you need to manually make sure that you actually modify all the right properties, meaning possible errors and mistakes.

Also, the Variant Manager can only alter actor’s attribute, and cannot interact with the Level Blueprint, which is where some of the scenario is implemented, and where we actually need to know the varying parameter’s value. This could be solved by adding empty actors acting as proxies, or trying to move the logic outside the Level Blueprint and into individual actors (which is a good practice anyway).

Finally, the Variant Manager’s UI isn’t very intuitive, and quickly becomes difficult to navigate and read when you have many variants. The Structure + Data Table combo is way easier to use in my opinion.

We’ll see where that gets us

As we’re just starting to use Unreal Engine, and since driving simulation experiments are always changing, our whole Scenario Variants concept and implementation are just an answer to some of today’s problems. We’ll have to see how things evolve in the future, and maybe once more adapt the way we build scenarios and experiments. Thankfully, our tools are flexible, and pretty much anything we can think of is possible.