Scenarios

An important and critical stage in driving simulator experiments is scenario authoring. We want to offer as much control as possible to researchers, allowing them to build any experiment they can imagine. But we also want this process to be as easy and intuitive as possible, so that non-experts can start working on their scenario as early as possible in the experiment design phase, allowing for quick and iterative development.

OpenSCENARIO

After OpenDRIVE was initially released, the PEGASUS consortium started to work on an even more ambitious standard: OpenSCENARIO.

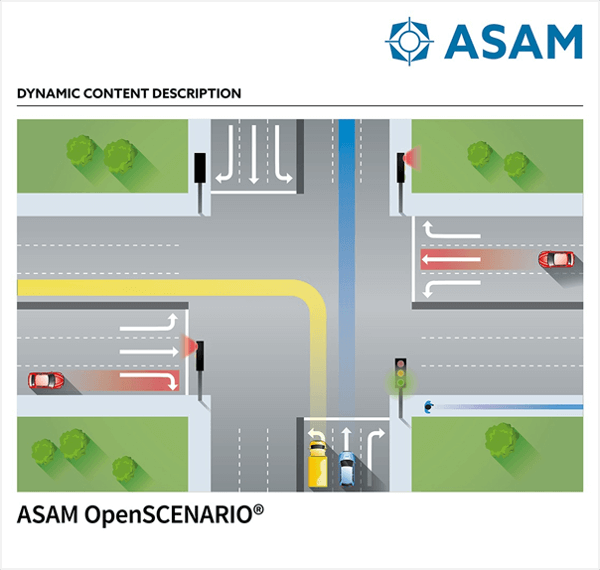

ASAM OpenSCENARIO defines a file format for the description of the dynamic content of driving and traffic simulators. The primary use-case of OpenSCENARIO is to describe complex, synchronized maneuvers that involve multiple entities like vehicles, pedestrians and other traffic participants.

In the same way as OpenDRIVE, OpenSCENARIO is currently between two versions. Its 1.x release is still being worked on, all the while a much more ambitious 2.0 Concept is nearing release. Even if the end goal is for the two releases to converge, right now the standard is in a weird place.

It doesn’t help that, just as the beginning as OpenDRIVE, tooling is not quite there yet. Even though you can find some players (like esmini), I don’t have knowledge of any editor out there. I know that VectorZero was working on a Scenario Editor before it was bought by Mathworks, but no news on that. The current “two versions” state of the standard definitely doesn’t help anyone looking to fill that space.

That alone could be enough to deter us from using OpenSCENARIO, but I’m not really pleased with the standard itself. I haven’t spent much time studying it, but the 1.x, and its XML format, was too restrictive in its scenario definition, and I’ve found quite a few examples of scenarios we had previously implemented that wouldn’t have been possible with this standard.

The 2.0 Concept release, on the other hand, is too broad in coverage, ranging from automated testing for ADAS development, to driver model, and more. Last I checked, they even had their own Domain-specific language, which might be a good idea in theory, but doesn’t really align with our “easy and intuitive” philosophy.

So I’m not a big fan of OpenSCENARIO, but I’m still following their work, hoping that the future will bring more features in alignment with our “simple” driving simulation requirements.

What are scenarios anyway?

One reason why OpenSCENARIO doesn’t really fit our needs is because we tend to push the definition of what a scenario is. As an engineer, I’m always looking for new ways to allow researchers to expand simulator experiments beyond the current state of the art. We’re finding new and innovative ways to study drivers’ behavior.

One example is a study by Jonathan Deniel, where he looked at automated driving effects on driver’s decision-making. To do that, participants experienced multiple autonomous lane-changes, and based on their feedback for each, custom scenarios were procedurally generated at runtime to have more in-depth insights for each participant.

Another example is a complex study on take-over from automated driving in critical situations, where we designed and tested multiple HMIs to help the driver take over. For this experiment, we had to implement various innovative HMIs, sometimes requiring complex interactions, and develop scenarios to make it so that each one could be run with each HMI.

In our latest experiment, which studies CAV-pedestrian interactions, we made basic modular scenario elements, allowing combination of those to create a very wide range of scenario variants (more on that later!). With our modular elements, we were able to easily change the CAV’s braking pattern, the pedestrian’s behavior (e.g. making a “thank you” gesture), or even buildings and itineraries (to ensure that the participant wouldn’t have an habituation effect from driving around the same city). The modular units were tailored-made for this project, but the idea can be applied to any driving simulation experiment.

Those examples illustrate some ways in which we’re expanding the usual definition of what a scenario is, allowing researchers to study more subjects at greater depth, and requiring agile development of the platform.

Beyond scenarios: Passation

Scenarios are often considered as the “unit” of the experiment. Your study has X scenarios, you run them in different orders, and that’s it.

However, for us, that’s not really how experiments actually go. Most have questionnaires of various forms, after some or all scenarios. Some experiments include playing videos (e.g. to induce an emotion), also at different times.

So we added the idea of Passation into our platform. Passation is French word we use for a single run of the experiment, like a “test period”. But I’ve never found a translation I liked, so I decided to english-ize the word.

A Passation is the combination of all the activities that the participant will go through. You can think of it as a “meta-scenario”. For the most basic experiment, it’s just a series of scenarios. But, as with the examples mentioned above, it can include much more than that.

With Passation, the researcher configures beforehand all the activities, the various orders that they can follow, etc. Once this is done, running a Passation is just a single button press. When your participant gets into your facilities, you start the process, and the platform takes care of the rest. The experimenter only has to provide input when the experiment design requires it. Otherwise, human intervention is not required. This means less work for the experimenter, less expertise required as to how to run the platform, less risk of manual error (e.g. wrong scenario started).

Using our Passation system, we’ve been able to reduce the overall length of experiments by removing human interventions. We’ve also made new things possible, as any activity, not just scenarios, can now be included at any point in an experiment.

Scenarios in Unreal Engine

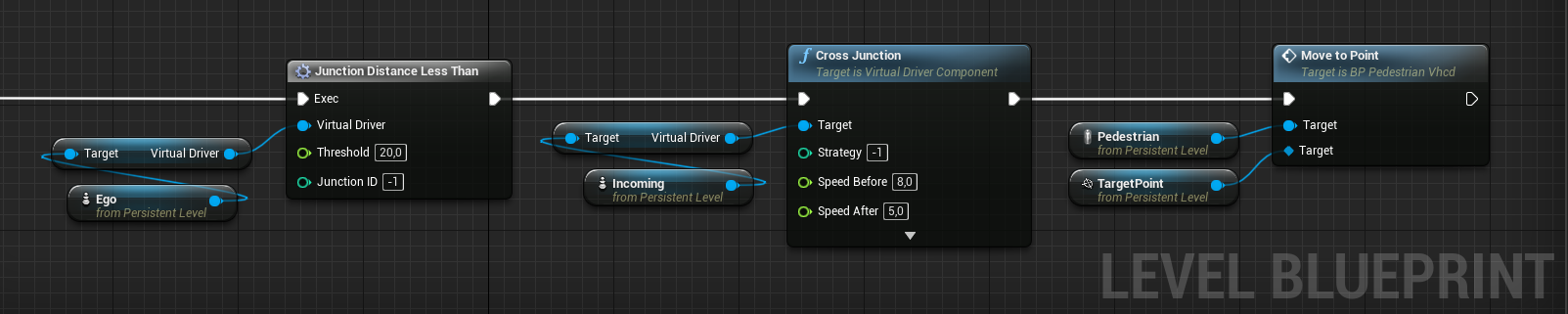

So how do we implement all of those scenarios in Unreal Engine? The Level Blueprint is the best place to start. In Unreal Engine, a Level (or map) is roughly the equivalent of what we, in the driving simulation world, call a scenario. And a level has its own special Blueprint, which has access to all actors within your level, therefore making it easy to add conditions and actions for what to do and when to do it.

Above is a very basic example taken from our driving simulator, which makes use of some features we added to the engine. Basically, this just says that when the vehicle Ego is closer than 20m from the next junction, the car named Incoming will turn left (-1) at the junction, and a Pedestrian will start moving to a point previously placed in the scene. Simple as that!

Of course this example isn’t exactly “pushing the boundaries” of what a scenario is, but it’s just showing how to do a basic scenario in our platform. Starting from that, we can easily scale up to the more complex and innovative examples that we’ve discussed in this post.